Last fall, a 7-inch injection well pipe ruptured 500 feet below the surface of Los Angeles, after ferrying natural gas for six decades. The resulting methane leak is now being called one of the largest environmental disasters since the BP oil spill, has pushed thousands of people out of their homes, and has quickly become the single biggest contributor to climate change-causing greenhouse gas emissions in California. But it’s not the first time this well sprang a leak—and Southern California Gas Company (SoCalGas), which owns and operates the well, knew it.

Last fall, a 7-inch injection well pipe ruptured 500 feet below the surface of Los Angeles, after ferrying natural gas for six decades. The resulting methane leak is now being called one of the largest environmental disasters since the BP oil spill, has pushed thousands of people out of their homes, and has quickly become the single biggest contributor to climate change-causing greenhouse gas emissions in California. But it’s not the first time this well sprang a leak—and Southern California Gas Company (SoCalGas), which owns and operates the well, knew it.

Over the past three months, engineers have had a terrifically difficult time plugging the leak. Normally in the case of a methane leak, a column of fluid would be pumped down into the well, to stem its tide. But with this particular well, that hasn’t been working. Instead, workers must drill down to the base of the well, 8,000 feet underground, creating a relief well to relieve the incredibly high pressure of the leak. Only then can the leak be repaired safely.

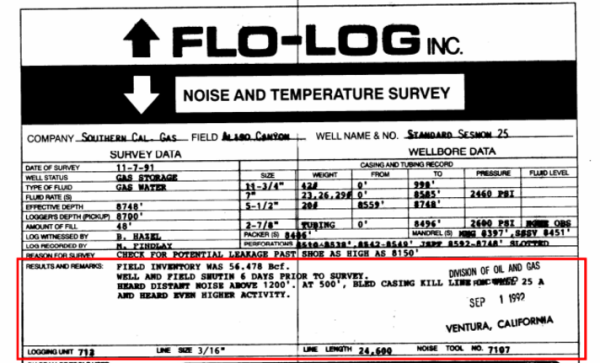

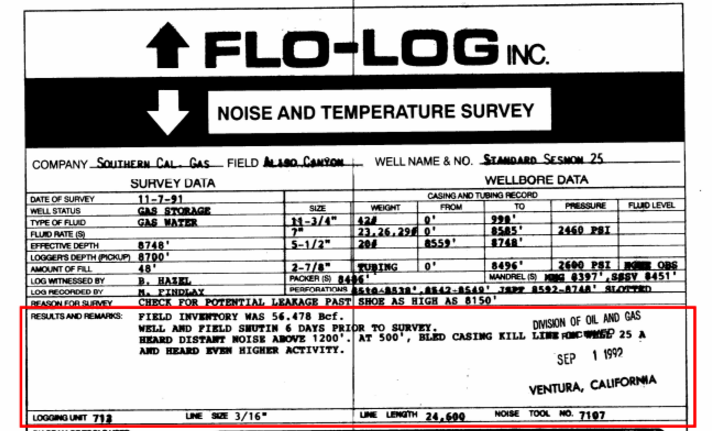

So who’s to blame for a leak that cannot be stopped? Aging natural gas equipment may have contributed. According to documents filed with the California Division of Oil, Gas & Geothermal Resources, this particular well, referred to as Standard Sesnon 25, was originally drilled in 1953, and showed signs of leakage 24 years ago, in 1992. Inspectors reported that they could hear the leak through borehole microphones.

Gene Nelson, a professor of physical science at Cuesta College in San Luis Obispo, California who has seen the document, said that he found it “appalling that SoCalGas did not identify this as a well to shut off,” after receiving this feedback.

There have been other problems documented at this facility before. And in 2014, inspectors at the wells documented corrosion and negative integrity trends.

In 2013, SoCalGas applied for and received money to do upgrades on equipment like safety valves—money that the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) says should have been used to prevent a leak like this. The regulatory decision filing shows that SoCalGas was granted $898,000 per year (in addition to the regular fund of about $3 million per year for repairs) to replace 5 percent of its safety valves at Aliso Canyon. According to EDF, these extra funds weren’t used as they should have been—to prevent a leak of this magnitude.

In 2014, written testimony to the California Public Utilities Commission by SoCalGas Director of Storage Operations Phillip Baker documented corrosion and negative integrity trends in the aging pipeline.

“Without a new inspection plan, SoCalGas and customers could experience major failures and service interruptions from potential hazards that currently remain undetected,” he wrote. The filing also noted that as of 2014, half of the company’s 229 storage wells were over 57 years old, and 52 wells were more than 70 years old.

“The company should be holding themselves to highest standard of care,” said Tim O’Connor, Director of California oil and gas for EDF, adding that SoCal should have had emergency plans in place to prevent long-term leaks from occurring. “This leak is a symptom of a larger issue—aging oil and gas infrastructure. We just don’t have a system to properly deal with storage leaks yet.”

Other safety issues have been pointed out recently, too. Earlier this month, The LA Times reported that attorneys representing some of the 1,000 residents suing SoCalGas over the leak claim the company failed to replace an important safety valve that was removed in 1979—a valve that could have stopped the current leak in its tracks. The plaintiffs also allege that the company again identified leaks at the site five years ago, but never implemented plans to fix them.

When pressed about the age of the pipes and the safety history of the well, a spokesperson for Sempra Utilities, the company that owns SoCalGas, said that the company performs daily well checks, and that this well had passed its last inspection:

Over time, the technology to monitor and operate underground gas storage field has developed steadily, and our facilities are at the forefront of safety controls and procedures. In addition, all our operations are closely monitored for compliance with the safety standards of the California Public Utilities Commission, the Division of Oil and Gas, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, and local fire departments.

Now, three months after the pipe first burst,, Gov. Jerry Brown has proclaimed a state of emergency in California. The declaration grants the state more powers to oversee the response, gives more authority to health officials, forces the utility to maximize its gas withdrawals, and ramps up safety inspections at the Aliso Canyon Underground Storage Facility in Porter Ranch—a neighborhood of Los Angeles where over 100,000 pounds of methane are now being pumped into California’s air every hour. The proclamation will likely allow more funds to be diverted to assist in cleanup efforts, and creates an independent panel to assess what went wrong with the leak and to assess its impact on human health.

http://motherboard.vice.com/read/the-company-behind-las-methane-disaster-knew-its-well-was-leaking-24-years-ago

Sign up on lukeunfiltered.com or to check out our store on thebestpoliticalshirts.com.