At a time when the Fed is already monetizing the entire US budget deficit thanks to helicopter money, sparking conversations about the utility of taxation, and when a Biden administration is set to at least try and roll back most of the Trump tax cuts, the last thing the population wants to hear about is even more taxes.

Yet in a “modest proposal” from Deutsche Bank, the bank argues that in a time of pervasive covid shutdowns, “those who can work from home (WFH) receive direct and indirect financial benefits and they should be taxed in order to smooth the transition process for those who have been suddenly displaced.”

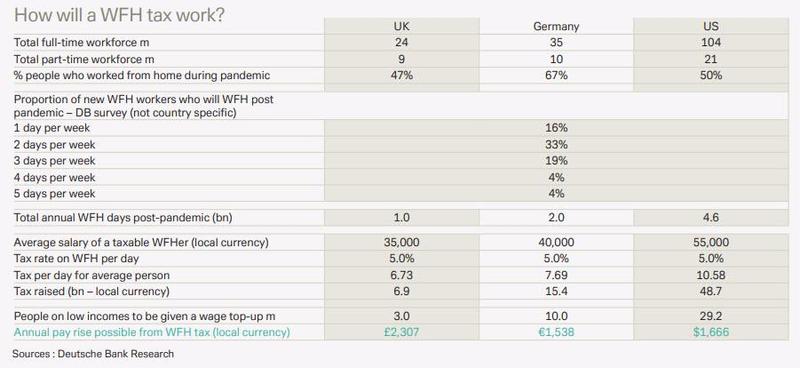

In other words, the argument goes that working from an office is somehow punitive, and since WFH during the pandemic leads to “many benefits” as a resulting “disconnecting themselves from face-to-face society” a 5% tax for each WFH day “would leave the average person no worse off than if they worked in the office.” The bank calculates that such a tax could raise $49bn per year in the US, €20bn in Germany, and £7bn in the UK. “That can fund subsidies for the lowest-paid workers who usually cannot work from home.”

In the report written by DB strategist Like Tumpleman, he argues that the popularity of WFH was growing even before the pandemic: “between 2005 and 2018, internet technology fuelled a 173 per cent increase in the number of Americans who regularly worked from home. It is true that the overall proportion of people working from home before the pandemic was still small, at 5.4 per cent based on census data, but the growth was still way ahead of the growth in the overall workforce.”

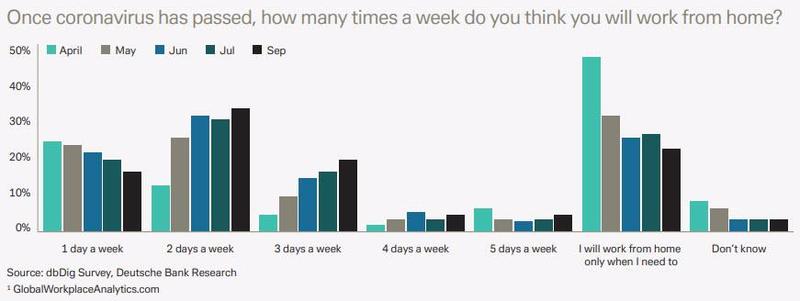

Naturally, the covid shutdowns have turbocharged that growth, and as a result the proportion of Americans who worked from home increased ten-fold to 56% during the pandemic. Many of these people will continue to work remotely for some time. Indeed, two-thirds of organizations say that at least three-quarters of their staff can work from home effectively, according to S&P Global Markets. Meanwhile, a DB survey shows that, after the pandemic has passed, more than half of people who tried out WFH want to continue it permanently for between two and three days a week.

This sudden shift to WFH means that, for the first time in history, “a big chunk of people have disconnected themselves from the face-to-face world yet are still leading a full economic life” as if that is somehow a bad thing.

It gets crazier: the bank claims that working in the comfort of one’s own home leads to a slew of financial benefits including:

- financial savings on expenses such as travel, lunch, clothes, and cleaning.

- indirect savings via forgone socializing and other expenses that would have been incurred had a worker been in the office.

- intangible benefits of working from home, such as greater job security, convenience, and flexibility.

- There is also the benefit of additional safety.

As if it is difficult to find someone who also sits in front of a computer all day long in Bangladesh and has the exact same skillset but would work for a fraction of the pay.

Yet those people who are working remotely are, according to DB, the equivalent of social parasites as they “contribute less to the infrastructure of the economy whilst still receiving its benefits” potentially extending the slump in national growth. In other words, the mere act of working from home makes you guilty of not propping up the economy!

That, according to Templeman “is a big problem for the economy as it has taken decades and centuries to build up the wider business and economic infrastructure that supports face-to-face working. If a great swathe of assets lie redundant, the economic malaise will be extended.”

In short, those who failed to develop the appropriate skillset and are “forced” to work in society – mostly employees of service companies – and who were unable to refused to educate and train themselves to be able to “enjoy” the benefits of work from home jobs which incidentally include sitting in front of a computer for hours on end and in some notable cases masturbating in front of a zoom conference call, have to be rewarded monetarily by all those who are lucky enough to not have to work in public.

While it would be easy to laugh and merely brush this idea off as another ridiculous policy proposal from a bank whose very existence would be very much in question had it not been for several rounds of generous taxpayer funded bailouts, since this is yet another grossly socialist proposal we are concerned it has a very high probability of passage not only in Europe but also in the US, especially if Democrats manage to pull of a “Blue wave” sweep in Georgia in January.

So far a WFH tax has merely been floated by a handful of Wall Street strategists; however once this idea gets more popular coverage, expect a groundswell of support for the idea which will promptly lead to yet another tax.

Below we republish the Deutsche Bank note in its entirety because it is clearly a blueprint for what’s to come:

A work-from-home tax, by Luke Templeman

For years we have needed a tax on remote workers – covid has just made it obvious. Quite simply, our economic system is not set up to cope with people who can disconnect themselves from face-to-face society. Those who can WFH receive direct and indirect financial benefits and they should be taxed in order to smooth the transition process for those who have been suddenly displaced.

The popularity of WFH was growing even before the pandemic. Between 2005 and 2018, internet technology fuelled a 173 per cent increase in the number of Americans who regularly worked from home1. It is true that the overall proportion of people working from home before the pandemic was still small, at 5.4 per cent based on census data, but the growth was still way ahead of the growth in the overall workforce.

Covid has turbocharged that growth. During the pandemic, the proportion of Americans who worked from home increased ten-fold to 56 per cent. In the UK, there was a seven-fold increase to 47 per cent. Many of these people will continue to work remotely for some time. Indeed, two-thirds of organisations say that at least three-quarters of their staff can work from home effectively, according to S&P Global Markets. Meanwhile, a DB survey shows that, after the pandemic has passed, more than half of people who tried out WFH want to continue it permanently for between two and three days a week.

The sudden shift to WFH means that, for the first time in history, a big chunk of people have disconnected themselves from the face-to-face world yet are still leading a full economic life. That means remote workers are contributing less to the infrastructure of the economy whilst still receiving its benefits.

That is a big problem for the economy as it has taken decades and centuries to build up the wider business and economic infrastructure that supports face-to-face working. If a great swathe of assets lie redundant, the economic malaise will be extended.

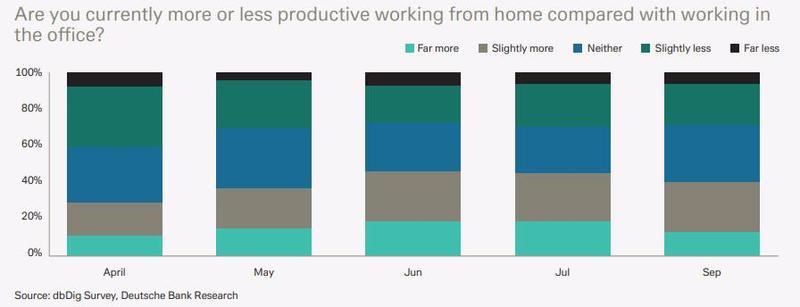

WFH is financially rewarding

WFH offers direct financial savings on expenses such as travel, lunch, clothes, and cleaning. Add to these the indirect savings via forgone socialising and other expenses that would have been incurred had a worker been in the office. Then there are the intangible benefits of working from home, such as greater job security, convenience, and flexibility. There is also the benefit of additional safety. The newly-discovered gains of home working, both tangible and intangible, all have value. And they generally outweigh the costs. The latter have mostly come in the form of additional mental stress of juggling work and children, and dealing with an imperfect home-office setup. These costs should not be underestimated, however, they usually pale in comparison with the gains. Hence why the vast majority of home workers want to continue remote working, on at least a part time basis, after the pandemic passes.

First, the tax will only apply outside the times when the government advises people to work from home (of course, the self-employed and those on low incomes can be excluded). The tax itself will be paid by the employer if it does not provide a worker with a permanent desk. If it does, and the staff member chooses to work from home, the employee will pay the tax out of their salary for each day they work from home. This can be audited by coordinating with company travel and technology systems.

The tax rate? Those who can work from home tend to have higher-than-average incomes. If we assume the average salary of a person who chooses to work from home in the US is $55,000, a tax of five per cent works out to just over $10 per working day. That is roughly the amount an office worker might spend on commuting, lunch, and laundry etc. A tax at this rate, then, will leave them no worse off than if they had chosen to go into the office. If we apply the same tax rate to workers in the UK with an assumed average WFH salary of £35,000, it works out to just under £7 per day. In Germany, a WFH salary of €40,000 leads to a tax of just over €7.50 per day.

A tax at this level means that neither companies or individuals will be worse off. In fact, companies may be far better off as the savings from downsizing their office will more than make up for the cost of the WFH tax they will incur.

How much will the tax raise?

First the US. Of the 104m Americans who work full time, half worked from home during the pandemic. That is up from the 5.4 per cent who already worked from home before the pandemic. Of that additional 45 per cent, our survey shows that three quarters want to work from home to some degree post-covid with 16 per cent wanting one day a week, 33 per cent two days, 19 per cent three days, 4 per cent four days, and 4 per cent five days.

Adding this up, there could be 4.2bn new days every year being worked from home postcovid. With an additional 394m days for those part time and full time staff who already work from home and are not self-employed, that gives 4.6bn WFH days per year. At an average salary of $55,000 and a tax rate of five per cent, the WFH tax will raise $48bn per year. The same calculation in the UK and Germany (using country specific WFH data and the salary levels assumed above) yields a tax take of £6.9bn and €15.9bn respectively.

What can the government do with this money?

In the US, the $48bn raised could pay for a $1,500 grant to the 29m workers who cannot work from home and earn under $30,000 a year (excluding those who earn tips). Many of these people are those who assumed the health risks of working during the pandemic and are far more ‘essential’ than their wage level suggests.

Similarly, in Germany, the €15.9bn raised could fund a €1,500 grant to the bottom 12 per cent of people in the country who have a standard of living equivalent to €12,600 (after adjusting for the size of their household). Similarly in the UK, the £6.9bn raised could provide a grant of £2,000 to the 12 per cent of those aged over 25 who work for the minimum wage. Of course, the exact amount of the grant could be based on an asymmetric tapering system.

Some will argue against the tax. They will say that engagement with the economy is a personal choice and they should not be penalised for making that decision. Yet, these people should remember that governments have always backsolved taxes to suit the social environment. Consider that in centuries past, when it was socially unpalatable in the UK to introduce an income tax, the government implemented a window tax. As society changed, the window tax was abolished and, eventually, an income tax was introduced. In the same way, as our current society moves towards a state of ‘human disconnection’, our tax system must move with it.

Best of all, a WFH tax does not merely subsidise businesses that have no long-term future. If, for example, a city-centre sandwich shop is no longer needed, it does not make sense for the government to support the business in the medium term. But it does make sense to support the mass of people who have been suddenly displaced by forces outside their control. Many will have to take low-paid jobs while they retrain or figure out their next step in life. From a personal and economic point of view, it makes sense that these people should be given a helping hand. It also makes sense to recognise that essential workers that assume covid risk for low wages. Those who are lucky enough to be in a position to ‘disconnect’ themselves from the face-to-face economy owe it to them.

Republished from ZeroHedge.com with permission

Sign up on lukeunfiltered.com or to check out our store on thebestpoliticalshirts.com.