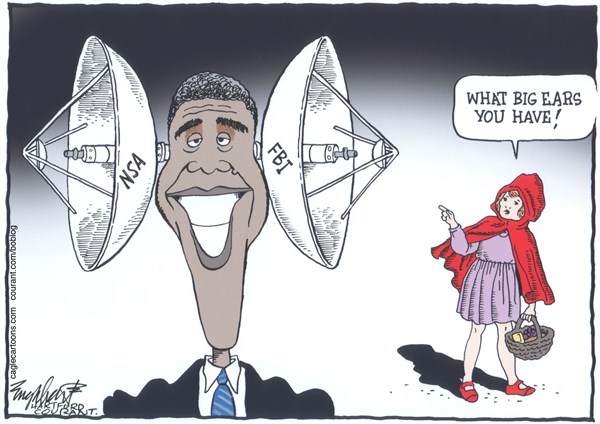

Newly released documents show the NSA chief was investing his money in commodities so obscure that most financial pros stay away.

BY SHANE HARRIS / http://www.foreignpolicy.com/

At the same time that he was running the United States’ biggest intelligence-gathering organization, former National Security Agency Director Keith Alexander owned and sold shares in commodities linked to China and Russia, two countries that the NSA was spying on heavily.

At the time, Alexander was a three-star general whose financial portfolio otherwise consisted almost entirely of run-of-the-mill mutual funds and a handful of technology stocks. Why he was engaged in commodities trades, including trades in one market that experts describe as being run by an opaque “cartel” that can befuddle even experienced professionals, remains unclear. When contacted, Alexander had no comment about his financial transactions, which are documented in recently released financial disclosure forms that he was required to file while in government. The NSA also had no comment.

Alexander’s stock trades were reviewed by a government ethics official who raised no red flags, and there are no indications the former spymaster did anything wrong. There are also no indications that the trades did much for Alexander’s personal wealth. Disclosure documents show that he earned “no reportable income” from the sale of commodity company stocks, meaning either that it was less than a few hundred dollars or that possibly he lost money on the deals.

Still, the trades raise questions about whether Alexander’s job gave him insights into corporations and markets that may have influenced his personal financial investments. The NSA, which Alexander ran for more than eight years, routinely spies on foreign governments and businesses, including in Russia and China, where the agency has attempted to gain insights into political decision-making, economic strategy, and the countries’ plans for acquiring natural resources.

The financial disclosure documents, which were released to investigative journalist Jason Leopold and published this month by Vice News, reveal nothing explicitly about why Alexander sold the shares when he did. On Jan. 7, 2008, Alexander sold previously purchased shares in the Potash Corp. of Saskatchewan, a Canadian firm that mines potash, a mineral typically used in fertilizer. The potash market is largely controlled by companies in Canada, as well as in Belarus and Russia. And China was, and is, one of the biggest consumers of the substance, using it to expand the country’s agricultural sector and produce higher crop yields.

“It’s a market that’s really odd, involving collusion, where companies essentially coordinate on prices and output,” said Craig Pirrong, a finance professor and commodities expert at the University of Houston’s Bauer College of Business.

“Strange things happen in the potash market. It’s a closed market. Whenever you have Russians and Chinese being big players, a lot of stuff goes on in the shadows.”

“Strange things happen in the potash market. It’s a closed market. Whenever you have Russians and Chinese being big players, a lot of stuff goes on in the shadows.”On the same day he sold the potash company shares, Alexander also sold shares in the Aluminum Corp. of China Ltd., a state-owned company headquartered in Beijing and currently the world’s second-largest producer of aluminum. U.S. government investigators have indicated that the company, known as Chinalco, has received insider information about its American competitors from computer hackers working for the Chinese military. That hacker group has been under NSA surveillance for years, and the Justice Department in May indicted five of its members.

Alexander may have sold his potash company shares too soon. The company’s stock surged into the summer of that year, reaching a high in June 2008 of $76.70 per share, more than $30 higher than the price at which Alexander had sold his shares five months earlier.

He may also have dodged a bullet. Shares in the company plunged in the second half of 2008, amid turmoil in the broader potash market. In 2009, “the bottom fell out of the market,” Pirrong said. Alexander may not have made a lot of money, but he also didn’t lose his shirt.

That didn’t keep the intelligence chief out of the trading game. In October 2008, in the midst of the potash downturn, Alexander purchased shares in an American potash supplier, the Mosaic Company, based in Plymouth, Minnesota. It was a good time to buy: On the day of the purchase, the stock closed at $33.16, having plummeted from highs of more than $150 per share during the summer.

But inexplicably, Alexander sold the shares less than three months later, in January 2009. The stock had barely appreciated in value, and Alexander again disclosed “no reportable income.”

The timing of both the potash and aluminum sales in January 2008 is also intriguing for political reasons. In the spring of 2008, shortly after Alexander sold his positions, senior U.S. officials began to speak on the record for the first time about the threat of cyber-espionage posed by Russia and especially China. Public attention to the intelligence threat was higher than it had been in recent memory. The optics of the NSA director owning stock in a company that his own agency believed may have been receiving stolen information from the Chinese government would have been embarrassing, to say the least.

In May 2008, four months after Alexander sold the shares, Joel Brenner, who at the time was in charge of all counterintelligence for the U.S. government and had previously served as the NSA’s inspector general, gave an interview to me when I was withNational Journal and accused China of stealing secrets from American companies “in volumes that are just staggering.” Brenner’s comments came just three months ahead of the opening of the 2008 Olympic Games in Beijing. He eventually went on national U.S. television to warn Americans attending the games that they were at risk of having their cell phones hacked.

U.S. officials at the time said that computer hackers in both China and Russia were routinely breaking into the computers of American businesses to steal proprietary information, such as trade secrets, business strategy documents, and pricing information. Eventually, Alexander himself went on to call state-sponsored cyber-espionage “the greatest transfer of wealth” in American history, blaming it for billions of dollars in losses by U.S. businesses and a loss of competitive advantage.

By 2009, Alexander held no more direct shares in any foreign companies, his records show. His financial transactions while in government apparently garnered no additional scrutiny beyond a standard review by ethics officials, who found no violations. Under official rules governing conflicts of interest, a government employee is prohibited from owning more than $15,000 in holdings of a company “directly involved in a matter to which you have been assigned.” For Alexander, spying on foreign governments and protecting the United States from cyber-espionage would seem to meet that criteria. But his records indicate that he never owned in excess of $15,000 in any foreign company.

The financial disclosure forms don’t say when Alexander bought his shares. Citing ethics rules, the NSA told Leopold that it was only required to release six years’ worth of information, leaving a gap between 2005, when Alexander started at the NSA, and 2008, the first year for which the agency released his financial information. But there’s nothing in the documents that states Alexander used a blind trust, suggesting that he either made the trading decisions himself or was aware of them if they were handled by a broker or advisor.

U.S. officials have long insisted that the information that intelligence agencies steal from foreign corporations and governments is only used to make political and strategic decisions and isn’t shared with U.S. companies. But whether that spying could benefit individual U.S. officials who are privy to the secrets being collected, and what mechanisms are in place to ensure officials don’t personally benefit from insider knowledge, haven’t been widely discussed.

Alexander has arguably blurred the lines between his private interests and public obligations before.

Alexander has arguably blurred the lines between his private interests and public obligations before. In July, Foreign Policyreported that he had filed patents for what he described in an interview as a “unique” approach to detecting malicious hackers and intruders on computer networks. But that technology was directly informed by the years Alexander spent at the NSA and as the head of U.S. Cyber Command, when he was responsible for detecting cyber-intrusions on military and intelligence agency computer networks.”There is no easy black-and-white answer to this,” Scott Felder, a partner with the law firm Wiley Rein in Washington, said at the time, adding that it’s not uncommon for government employees to be granted patents to their inventions.

But another of Alexander’s business deals has also raised questions about whether he continues to benefit from classified information and access to top players at his old agency.

In an employment deal that prompted an internal investigation at the NSA and inquiries from Capitol Hill, Alexander arranged for the agency’s chief technology officer, Patrick Dowd, to work part time for a new cybersecurity consulting firm that Alexander started this year after leaving the NSA and retiring from the Army with a fourth star. Experts said the public-private setup was highly unusual and possibly unprecedented.

Reuters revealed the arrangement last week, and on Tuesday, Oct. 21, with pressure building from lawmakers to investigate, Alexander said that he was severing the relationship with Dowd. “While we understand we did everything right, I think there’s still enough issues out there that create problems for Dr. Dowd, for NSA, for my company,” Alexander told Reuters when explaining why he scuttled the deal. Alexander’s company, IronNet Cybersecurity, is based in Washington, and he has said he might charge clients as much as $1 million per month for his expertise and insights into cybersecurity.

Sign up on lukeunfiltered.com or to check out our store on thebestpoliticalshirts.com.