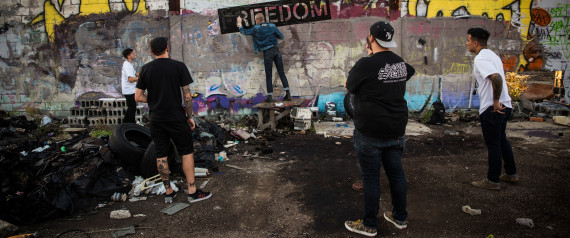

DETROIT, MI – SEPTEMBER 04: Members of the band “Freedom” spray paint their name on a wall at the abandoned Packard Automotive Plant on September 4, 2013 in Detroit, Michigan. (Photo by Andrew Burton/Getty Images)

Source: Huffington Post

The urban poor in the United States are experiencing accelerated aging at the cellular level, and chronic stress linked both to income level and racial-ethnic identity is driving this physiological deterioration.

These are among the findings published this week by a group of prominent biologists and social researchers, including a Nobel laureate. Dr. Arline Geronimus, a visiting scholar at the Stanford Center for Advanced Study and the lead author of the study, described it as the most rigorous research of its kind examining how “structurally rooted social processes work through biological mechanisms to impact health.”

What They Found

Researchers analyzed telomeres of poor and lower middle-class black, white, and Mexican residents of Detroit. Telomeres are tiny caps at the ends of DNA strands, akin to the plastic caps at the end of shoelaces, that protect cells from aging prematurely. Telomeres naturally shorten as people age. But various types of intense chronic stress are believed to cause telomeres to shorten, and short telomeres are associated with an array of serious ailments including cancer, diabetes, and heart disease.

Evidence increasingly points to telomere length being highly predictive of healthy life expectancy. Put simply, “the shorter your telomeres, the greater your chance of dying.”

The new study found that low-income residents of Detroit, regardless of race, have significantly shorter telomeres than the national average. “There are effects of living in high-poverty, racially segregated neighborhoods — the life experiences people have, the physical exposures, a whole range of things — that are just not good for your health,” Geronimus said in an interview with The Huffington Post.

But within this group of Detroit residents, the ways in which race-ethnicity and income were associated with telomere length were strikingly varied.

White Detroit residents who were lower-middle-class had the longest telomeres in the study. But the shortest telomeres belonged to poor whites. Black residents had about the same telomere lengths regardless of whether they were poor or lower-middle-class. And poor Mexicans actually had longer telomeres than Mexicans with higher incomes.

Geronimus said these findings demonstrated the limitations of standard measures — like race, income and education level — typically used to examine health disparities. “We’ve relied on them too much to be the signifiers of everything that varies in the life experiences of difference racial or ethnic groups in different geographic locations and circumstances,” she said.

According to Geronimus, it’s important to consider not just racial-ethnic identity, but also “the extent to which it is validated, or discriminated against, or even understood within your everyday life experience” can affect an individual’s health dramatically, Geronimus said. “Race is not race is not race. Poverty is not poverty is not poverty. Early health deterioration is sensitive to a broad range of life experiences.”

When Ethnic Identity Impacts Health

So why did poor Mexicans in this study have longer (i.e., generally healthier) telomeres than the nonpoor Mexicans? Geronimus first noted that most poor Mexicans in Detroit were either first-generation immigrants to the United States or part of close-knit ethnic enclaves. In contrast, nonpoor Mexicans were more often born in the U.S. and were more integrated into American culture through work or school.

“If they’re immigrants, then they come with a different cultural background and upbringing that didn’t stress that as Mexicans they were somehow ‘other’ or ‘lesser’ than other Americans,” said Geronimus. “They come with a set of support systems and with a cultural orientation that doesn’t undermine their sense of self-worth. They then often live in these ethnic enclaves, many of them don’t speak anything other than Spanish, and so they’re not interacting with Americans who view them as ‘other’ or who treat them badly. It’s not that they’re immune to that treatment but they’re not as sensitive to it and they also just don’t experience it as often.”

On the other hand, nonpoor Mexicans are more likely to be “exposed to some of the negative views of Mexicans held by some Americans, the conflation of anyone of Mexican origin as being an immigrant or possibly an undocumented immigrant, or even more neutral assumptions like ‘they must speak Spanish,’ or ‘they don’t understand English.'” Ironically, in seeking to become socially mobile and avoid the stress of poverty, these lower-middle-class Mexicans may face even more pronounced stressors tied to their ethnic identity.

Geronimus said the findings of the new study, based on quantitative physiological research, “line up perfectly” with previous ethnographic studies of Mexicans in Detroit done by another researcher, Dr. Edna Viruell-Fuentes of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. A health site summarized the conclusions of Viruell-Fuentes’s work:

In 2007, Viruell-Fuentes interviewed 40 first- and second-generation Mexican immigrant women in the Detroit area. Though she points out that racial dynamics are hard to measure, based on her interviews Viruell-Fuentes believes that “identifying experiences that are discriminatory may be a learned process.” Often first-generation women characterized certain interactions as simply rude, while second-generation women labeled similar experiences as discriminatory. […]

In a 2012 review paper, Viruell-Fuentes pointed out that the first generation tends to stay within ethnic enclaves that may buffer some of the social disadvantages that immigrants face. “For the second generation, what I think is different, is that they have a lifelong exposure to an environment that stigmatizes their identity, which in turn can affect their health negatively,” she said.

“Often the question is raised, what is it about immigrants that makes them more resilient?” Viruell-Fuentes said. “But the other piece of the question for me is, what is it about the United States that is damaging to people’s health?

Other health effects tied to race-ethnicity identified in the new study could be viewed as counterintuitive. Income level seemed to have no effect on the telomere lengths of black Detroit residents, while the telomeres of poor whites were significantly shorter than those of nonpoor whites. Why?

The study’s authors noted:

Much research suggests the separation between poor and nonpoor blacks in everyday life is less marked than between poor and nonpoor whites. Not only do blacks tend to have greater residential proximity owing to residential segregation, but often poor and the nonpoor blacks are members of the same families and social networks, practice reciprocal obligations, or have similar experiences of cycling between low and moderate incomes.

Income instability among middle-class blacks reflects job insecurity, a relative lack of conventional assets or wealth to tide them over in rough times, or a network-level division of labor whereby some are expected to contribute to family economies through income generating work, others contribute by seeing to the family caretaking needs that facilitate the employment of others, and still others provide important services and skills as barter exchange.

Researchers also highlighted the hypersegregation in the Detroit area. “Most blacks in our sample live almost exclusively with other blacks (97% of Eastside Detroit residents are black) or are the majority group in integrated neighborhoods (e.g., 70% of Northwest Detroit residents are black), [and] whites are a clear minority in all of our Detroit areas (ranging from 2% to 21% of residents).”

They found that associations between telomere length and perceptions of neighborhood physical environment and neighborhood satisfaction were strongest for blacks, and questioned whether “safety stress, physical environment, and neighborhood satisfaction tap into a more global construct of how black participants experience Detroit neighborhoods, which on balance may be more positively than for white or Mexican participants.”

In contrast, regarding white Detroit residents, the researchers wrote, “Perhaps with the exodus of most whites and many jobs from Detroit, the shrinking benefits of labor union membership and public pensions, and the overall reduction in taxation-based city services, the poor whites who remain are particularly adversely affected by the social and ecological consequences of austerity urbanism. Lacking the financial resources, social networks, and identity affirmation of the past, remaining Detroit whites may have less to protect them from the health effects of poverty, stigma, anxiety, or hopelessness in this setting.”

Geronimus summarized, “I think a lot of people just don’t understand how bad it is for some Americans. It’s disproportionately people of color given our history of residential segregation and racism, but it’s also anyone who gets caught. It’s like the dolphins who get caught in the fishing nets, it’s anyone who gets caught there. If anything, some of our evidence suggests that whether it’s the poor Mexican immigrant or the African-Americans who have been discriminated against and dealt with hardship for generation after generation, they’ve developed systems to cope somewhat that perhaps white Detroiters haven’t. So there’s great strength in these populations. But it’s not enough to solve these problems without the help of policymakers and more emphatic fellow citizens.”

Telomeres, Health, And Social Justice

One co-author of this new study is Dr. Elizabeth Blackburn. She helped to discover telomeres, an achievement that won her the Nobel Prize in physiology in 2009.

When her research began in the mid-1970s, Blackburn worked on identifying telomeres in one-celled organisms she laughingly calls “pond scum.” But over the years, as she and other scientists discovered the far-reaching human health implications of telomeres, her focus shifted.

“So much of what makes people either well-being or not is not coming from within themselves, it’s coming from their circumstances. It makes me think much more about social justice and the bigger issues that go beyond individuals,” she said in an interview from her office at the University of California San Francisco.

Blackburn believes that vital questions relevant to social policy have remained unanswered because the issues were highly complex and it was easy to question data from qualitative research methods, like people’s questionnaire answers about their personal experiences and perceptions. “When something’s really hard to assess, the easy thing is to dismiss it. They say it’s soft science, it’s not really hard-based science.”

But now telomere data is providing a new way to quantitatively analyze some of these complex topics. Blackburn ticked off a list of studies in which people’s experiences and perceptions directly correlated with their telomere lengths: whether people say they feel stressed or pessimistic; whether they feel racial discrimination towards others or feel discriminated against; whether they have experienced severely negative experiences in childhood, and so on.

“These are all really adding up in this quantitative way,” she said. “Once you get a quantitative relationship, then this is science, right?”

Sign up on lukeunfiltered.com or to check out our store on thebestpoliticalshirts.com.